I’m a Scientist with Learning Disabilities and That’s Okay!

Post doc Collin Diedrich discusses his experiences as a learning disabled scientist.

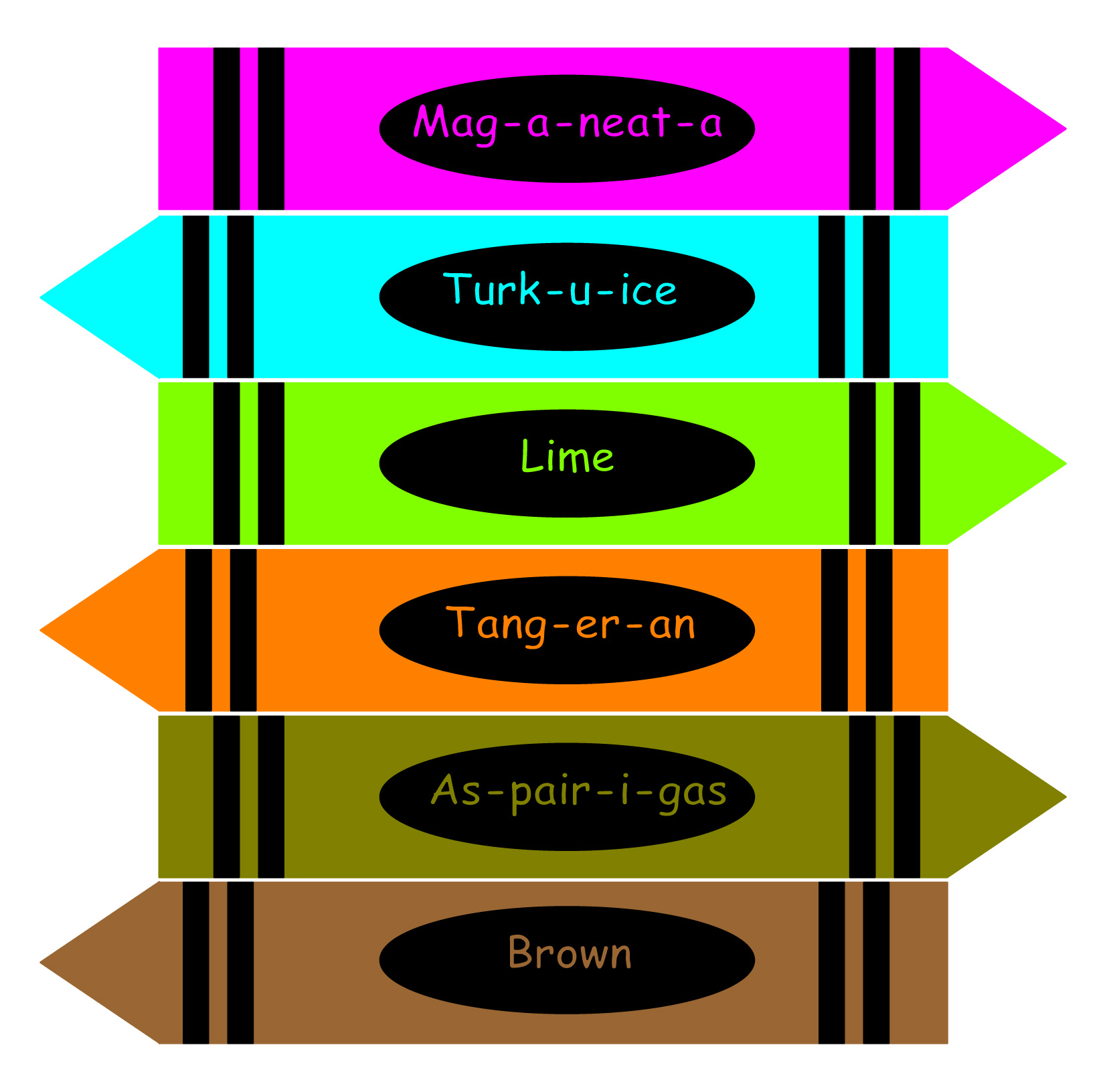

About a month ago, I was playing with my 3yr old niece, drawing pictures with Crayola Crayons. She pulled out a purplish color and asked me what it was. I dutifully read the name, as phonetically as I could, “MAG-A-NEAT-A… what the hell is MAG-A-NEAT-A?” We all laughed, and my brother (the dad) intervened: “It’s MA-GEN-TA.” I told my niece I probably am not the best person to read her these names. Also that I should learn to use better language around 3yr olds.

I read between a 6th and 9th grade level and have a language processing speed in the bottom 14% of the population. I have an unspecified reading disorder (DSM-IV 315.00) and learning disorder (DSM-IV 315.9). Despite these learning disabilities (LDs) and my love-hate relationship with Crayola Crayons, I have a PhD in molecular virology and microbiology and I am a second-year post doc at University of Cape Town. My life is not a mental contradiction.

I want to help address the misinformed stigma that being learning disabled is synonymous with being unintelligent. What does it mean to be intelligent? Is it the ability to learn new information efficiently? The ability to process complex information quickly? Is it more important to intelligence to comprehend what you read, or to effectively communicate through your words (either written or spoken)? Intelligence is ambiguous. Maybe intelligence is similar to former US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s opinion on obscenity: “I know it when I see it.”

On the surface, I don’t make the “that guy’s really intelligent” cut in pretty much every aspect of my life. I have a hard time learning names, reading menus, following directions when driving, I get lost in conversations that are happening too quickly, and almost always give up on long online articles that require you to push that dreaded ‘go to next page’ button (silly New York Times). Anything related to words–consuming, understanding, or disseminating them to new people–is incredibly difficult for me. This makes me ask, “Is it possible for me to be successful in a field that essentially uses ‘intelligence’ as a prerequisite?” Without a doubt!

Although I may be destined to watch TV or listen to audiobooks as opposed to sitting down and reading a good book, I feel intelligent where it counts in my field: understanding the research on how HIV manipulates TB diseased sites. For reasons that elude me to this day, I’ve learned and retained the literature incredibly well and how it relates to my experiments better than I know my birthday. I don’t remember authors and journals, but I do remember the experiments, results, figures, and how their conclusions compare to my work. I’m able to ask questions and design experiments that objectively allow me to examine my hypotheses. What this essentially means is that I feel intelligent at my day job but not during my everyday life and I’m okay with this.

I believe this inconsistency in intelligence puts a horrible strain on the millions of LD Americans. We usually struggle in school, score poorly on standardized tests (my GRE reading section was in the bottom 30-ish% of the population), and get intimidated by the ‘massive amounts of [insert the skill you’re bad at] that is/are necessary in [insert ideal job]’. Moving past those barriers is incredibly scary and have led to many sleepless nights, self doubt, personal hatred, and tears. I know this first-hand and I am about as privileged as it gets, being a white upper-middle class male American who has benefited tremendously from my dedicated parents who consistently advocated for me through high school and were able to afford weekly private tutoring from 1st to 12th grade. I can’t imagine what it must be like for students and adults with LDs that deal with even more inequalities. The educational system is designed to teach the ‘average’ student, which means that those with learning disabilities may not receive the help they need for success.

Scientists and engineers (S&E) with LDs is not unheard of: approximately 0.9% (311) of all (34531) S&E doctoral recipients in 2011 self identified as having one or more learning disorders. I wish these numbers were higher despite the extensive amount of reading or computing necessary for completion of these degrees and within a career. I wish I could say that individuals with LDs are more likely to succeed than their non-LD coworkers, but I honestly have no idea how LDs correlate to ‘success’ in S&E.

However, I do know that these individuals literally ‘think differently’ and have already demonstrated that they have figured out how to overcome their own limitations. Goal-orientation, perseverance, and passion have consistently been shown as some of the most important attributes to success. In my biased opinion, individuals with LDs will have to have these personality traits, giving them a paradoxical “leg up” in academia.

Sacrifices will have to be made on all sides and it may take the LD student longer than their non-LD peers to complete the same tasks. I was incredibly fortunate to have a PI in graduate school that allowed me to explain my data in our one-on-one meetings in a way that was comfortable with me, while expecting just as much from me as anyone else. Currently my boss at University of Cape Town has given me an incredible amount of freedom to begin a completely new project. My colleagues in my lab and within the entire department are also incredibly helpful, answering my questions without judgment, limiting the time I lose to painstakingly read research. I’ve been fortunate to be surrounded by scientists, friends, and family members that show me they care about me by not caring about my LD.

I hope schools will become more cognizant of identifying and helping students with LDs. I hope research program admission committees can look beyond test scores and GPAs when accepting new students (I was rejected from 7 out of 8 I applied for). I hope students are able to be open about their LDs with their PI’s, working together to find the most efficient and helpful ways to have meetings, write papers, perform experiments, and present results. I hope that no LD scientist or engineer feels like they’re alone. Most of all, I hope struggling LD students and adults are able to feel good about who they are.

Environments like this have helped me accept the fact that it doesn’t matter that I may be below the curve in a few intellectual areas. Intelligence, like pretty much everything else subjective, is on a spectrum and just because you may be lower than average in one or every single area, it doesn’t have anything to do with how good you will be at your job, whether that’s as a scientist, clinician, or business woman. Whether you have a LD, work with someone who does, or have no idea if anyone around has one or not, I implore you to keep an open mind about individuals with learning disabilities.

I’m curious if any readers can relate to this topic. Do you or anyone you know have LDs? Please share your stories in the comments or email me at Collin@ldphd.org. The more we open up about the fact that we, as LD individuals in various fields, are out in the world we can help change the stigmas.

Collin Diedrich received his PhD in Molecular Virology and Microbiology from the University of Pittsburgh. He is currently a post doc at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Collin has previously contributed to Speaking of Medicine. See his previous post: Gaining Perspective from Performing HIV/M. tuberculosis co-Infection Research in South Africa.

Collin Diedrich received his PhD in Molecular Virology and Microbiology from the University of Pittsburgh. He is currently a post doc at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Collin has previously contributed to Speaking of Medicine. See his previous post: Gaining Perspective from Performing HIV/M. tuberculosis co-Infection Research in South Africa.

Love this piece. Would make a great reoccurring column to address the many issues of LD.

Thank you for this. Confusing intelligence with disabilities is common. People misunderstand learning disabilities and other conditions that prevent people from realizing their full potential. I can only imagine the talent we’ve lost over generations. I’d love to see more writing related to this issue to educate the general public and to encourage folks with learning disabilities to keep marching on.

As a LD scientist (currently working as a postdoctoral fellow in Canada) who suffers from dyslexia I really appreciated this story. I know how much it sucks knowing your behide the curve and knowing alot of the basic skills people take for granted are hard for us but I think the important thing to remember is how our disabilities really shape and changes the way we see both working in labs and how we approach science.

As some one who has really relied on help from others for most of my life I never want anyone to feel the levels of helplessness and loneliness I have felt over the years. I will always help someone, no matter the disruption to my work. As a LD scientist you don’t get the luxury of arrogance, you have been humbled more times then you can remember and know there are more to come. This experience shapes us and allows us a level of empathy that other scientist may never be able to achieve.

As a researchers our struggle with our own imperfections also allows us to accept errors and the imperfections in our techniques and technologies which seem, in my experience, hard for others to even acknowledge. We understand limitations , we understand what they mean and how they shape what data can be accurately gain from an experiment. We also understand that mistakes can happen and that they may be due to a inheritance imperfection in an approach or technology and not the person doing the experiment themselves.

These experiences, I feel, make us valuable member of the S&E workforce. The fact that less the 1% of S&E grads share these experiences doesn’t shock me but I do think our unique prospective would enrich the scientific environment.

[…] I Am a Scientist with Learning Disabilities, And That’s OK https://blogs.plos.org/speakingofmedicine/2014/06/10/im-scientist-learning-disabilities-thats-okay/ […]

I greatly appreciate this article; it makes a very important point on an issue which has had a significant effect on my life. The stigma associated with having LDs/ADHD and intelligence is something which I too find very concerning, particularly as a scientist with ADHD, dyslexia and a “language deficit”. Yet even with LDs/ADHD I still was able to earn a degree in Physics, masters in Pharmacology, a doctorate in Physiology and am now a post-doc. However there still is a significant stigma attached with LDs/ADHD which keeps people from being open about it and even leaves me a bit hesitant to do so now. Sharing this information often results in people treating you like you are incompetent and unintelligent. And while neither of those things has to do with LDs/ADHD this is still the prevalent attitude from the scientific community and even one our society in general mistakenly holds. Like the author said LDs and intelligence/scientific acumen are not contradictory traits.

I have been very lucky to have gotten past the major academic hurdles LD/ADHD students have to additionally face but mostly this is because of a rare combination of luck and advantages I have had. Yet even with such advantages it was unnecessarily difficult and still I was almost locked into the special education track in school early on because of my LDs/ADHD. Grade and middle school were particularly challenging (truly much more so than any of my degrees at top schools) because of the mistaken perception that parameters like reading ability, spelling, handwriting and organization are the primary indicators of intelligence and effort.

This is simply not true for LD/ADHD students.

Because of this, it meant that until I figured out those couple non-LD/ADHD skills I lacked I could try my hardest at a subject and still do abysmally even if I knew perfectly well what was going on in the class. For LDs and particularly for ADHD, students continually get marked down in every subject for the same skills. Even in subjects where they should have otherwise excelled they are marked down for the same LD/ADHD parameters despite their irrelevancy to a particular subject matter. For those reading this without LDs/ADHD the effect is no different than continually giving out bad grades to a student that doesn’t read well and is late all the time meanwhile expressing that he is dumb and careless while ignoring that this is only the case because he is mostly blind. Obviously, this is needlessly frustrating and damaging to the student and their likelihood of success. Even when there are special education programs available it usually comes after many years of repeated exposure to such failures and it still very much carries the associated stigma of having LDs/ADHD from teachers and peers.

I think the problem can be aptly summed up by an Einstein quote. “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid.” Simply put I see this as the primary reason for why there are so few LD/ADHD scientists and why this myth of a link between incompetency and LDs persists, because we spend so much of our academic experience repeatedly being set up for failure starting at an early age and thus it becomes it’s the classic example of the self fulfilling prophecy.

The problem is not just that there are so few LD/ADHD scientists or the unjust atmosphere of incompetence imposed upon us, the problem is that LD/ADHD students have some of the highest dropout rates in the country despite having essentially the same intelligent levels as non-LD/ADHD students. This is an outrageous statistic.

Almost all schools evaluate the academic potential of a student first on organizational and attention parameters, then their ability to read and write and finally if those hurdles are passed, then and only then, they assess their intellectual ability and potential. I’m not trying to suggest that things like organization or reading comprehension aren’t very important skills to develop and have, of course they are, but these are only a handful of skills out of many needed to become a successful scientist and adult. These few parameters should not be used to gauge and resultantly limit a student’s educational and vocational prospects in the premature manner which they are being used.

No one fails English because they are bad at Math, no one fails Math because they are bad at Art, yet many intelligent and talented students are failing all of their classes simply because they are bad at sitting still for long periods of time or have trouble reading instructions. The reason why the misperception persists is because LDs/ADHD students exhibit a select collection of traits which are significantly and artificially stigmatized by the educational system from a very early age. As a society we have internalized this prejudice the way we internalize everything we are taught. The areas of LD/ADHD skill deficiency like reading, attention, organization, ability to follow verbal instructions etc need to be recognized as being on a scale which not everyone will or needs to have exceptional talent for. These skills need to be taught and assessed separately rather than penalizing the LD/ADHD student for the same few skills in every single class, especially when no instruction is ever given on how to improve most of these skills.

Everyone would greatly benefit if the stigma associated with LDs/ADHD could be eradicated, not just simply because it would be helpful for those of us with LDs in science now encountering these negative and inaccurate perceptions day to day, but mostly because it continues to do so much damage to the many bright and talented LD/ADHD students who’s education and future are being significantly limited by this systematic bias. For every PhD, MD or engineer with LDs/ADHD think of how many LD/ADHD adults there must be out there who are just as smart and would have been just as effective in those careers but were held back in their education because of the prevalent prejudicial belief that having LDs/ADHD means you are unintelligent or unable to succeed academically and in life. This is a tragic waste.

I know what I’m risking my openly admitting that I have LDs and even more so by admitting I have ADHD because I know firsthand the kind of negative reactions it can generate from even the most educated and well-intentioned people. But there needs to be more discussion of this topic. More people need to be willing to openly serve as examples so that the many LD/ADHD students can realize that just because they keep getting bad grades because their assignments are always a day late (despite their best efforts) or because they didn’t finish all of the reading in time (despite their best efforts), that this doesn’t mean they can’t become very successful scientists, medical doctors, engineers or any other academically situated profession.

The disproportionate negativity received for LD/ADHD traits effectually inhibits student from fully developing all of their other talents and abilities both overtly by denying access to upper level courses and subversively through the persistent additional penalties for these selected traits. This needs to stop. The fact that there are so few of us ADHD/LD students who make it into science, despite their sometimes increased association with traits like creativity and divergent thinking, is indicative of a major systematic failure on the part of the educational system which largely goes unrecognized by those in the upper levels of academia.

The conversation needs to be about more than just the prejudice experienced by those of us in science. The conversation needs to include the all of the factors which make it such an anomaly for an LD/ADHD scientist to even exist. The educational bias against those with LDs and ADHD is significant, hurtful, wasteful and long lasting.

So the most meaningful contribution to this issue I can make at this point is to post my name as another example of a scientist with LDs/ADHD and repeat that these are in no way contradictory traits.

[…] https://blogs.plos.org/speakingofmedicine/2014/06/10/im-scientist-learning-disabilities-thats-okay/ […]

Great article Collin! Many will benefit from reading it.

[…] I Am a Scientist with Learning Disabilities, And That’s OK […]

Thanks so much for the comment, Scott. I’m glad you liked the piece! I hope I can continue writing about this topic!

Hi CC, Thanks so much for the comment. I hope that over then next generations all ‘learning styles’ will be accommodated in the future at schools, work, and life.

Hi Nichollas, I can’t agree with you more! You bring up a wonderful point about ‘paying forward’ the help that you’ve received your whole life on others. Everyone needs help from time to time and it’s so important to give it when you can and ask for it when you need it.

Hi Kate, Thanks so much for this meaningful comment. I completely agree with you. I think that the only way more scientists with LDs/ADHD will make it in these careers is if a drastic change starts to happen in school, and most importantly, at home. As we learn more how people ‘learn and process information’ we’ll be able to help everyone excel. I really like your point that, “No one fails English because they are bad at Math, no one fails Math because they are bad at Art…”. It is so true that a lot of people assume that if you can’t do “X” well then you must be bad at “Z”. It’s my hope that the people that are fantastic at “X” will be able to just focus on that while not bothering with “Z”. We’ll let the people that are awesome at “Z” deal with it.

Thanks again for your detailed comment. I really do appreciate it.

Thanks so much, Dick!

Hi Collin. Your article should be considered a groundbreaking foundation stone in the field of education. You address beautifully the difference between learning and abilities. Established pedagogy mixes both and in the process discards many a talented and gifted ability endowed people.

I wish all the best in all your endeavors.

To Colin and everyone who commented, it’s really nice to talk about this issue openly amongst people who know what it’s like to suffer from LD and/or other conditions. I have ADHD and a number of comorbidities. Life can become needlessly difficult and after years of being afraid of science, I’m finally crawling back albeit slowly.

Does anyone know of organizations run by scientists with LD and other conditions that help folks with similar challenges?

The existing organizations I’m aware of approach these conditions as a general setback but I think a body that specifically addresses this issue in the context of entry into the sciences as well as talent retention will be particularly beneficial.

Having been through my own struggles, I want to take meaningful action to help.

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

[…] This post first appeared in The Public Library of Science Blog. […]

Thank you for this well written article! I work in a hospital where I’m part of a team who evaluates children for learning disorders in reading, math, and language. Your article expresses the very sentiments that we strive to tell families. Strong advocacy, recognition of strengths, and aligning with supportive educators and employers all contribute to building a successful academic and professional life. Thank you for sharing your perspective so beautifully.

Being the wife of a post doc you hear what goes on in colleges. My husband grew up in a different nation, but has made his way through blood, sweat and tears to his PhD. It’s not easy when scientists have terrible mentors, and ones that ask them in a rude way if they have a learning disability. Growing up in a nation completely different does not make you the most perfect writer, but I I think many mentors focus only on peoples writing skills rather then their science. America is very hung up in details. We should be rewarding students who see the bigger picture and make amazing discovery. After all Einstein was not American born. I am sure there are millions of scientists that have disabilities and never say a word about it, or they risk their career. Academia needs some help in the communication area.

I have a 13 year old daughter with a LD who has dreamt of being a biologist since she was old enough to know what a biologist is. As we stuggle our way through the frustrating school system in Canada that only seems to have room for one kind of learner, that dream often seems so unachievable. Your article and the responses to it give me much hope and the strength to keep pushing against the system – try break some barriers down so my daughter can have a fair shake at succeeding. Thank you so much!

Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid. — Albert Einstein

Cartoon image:

http://imgur.com/B5TgS