Pneumonia Affects People of All Ages: Interview with Carlos J. Orihuela

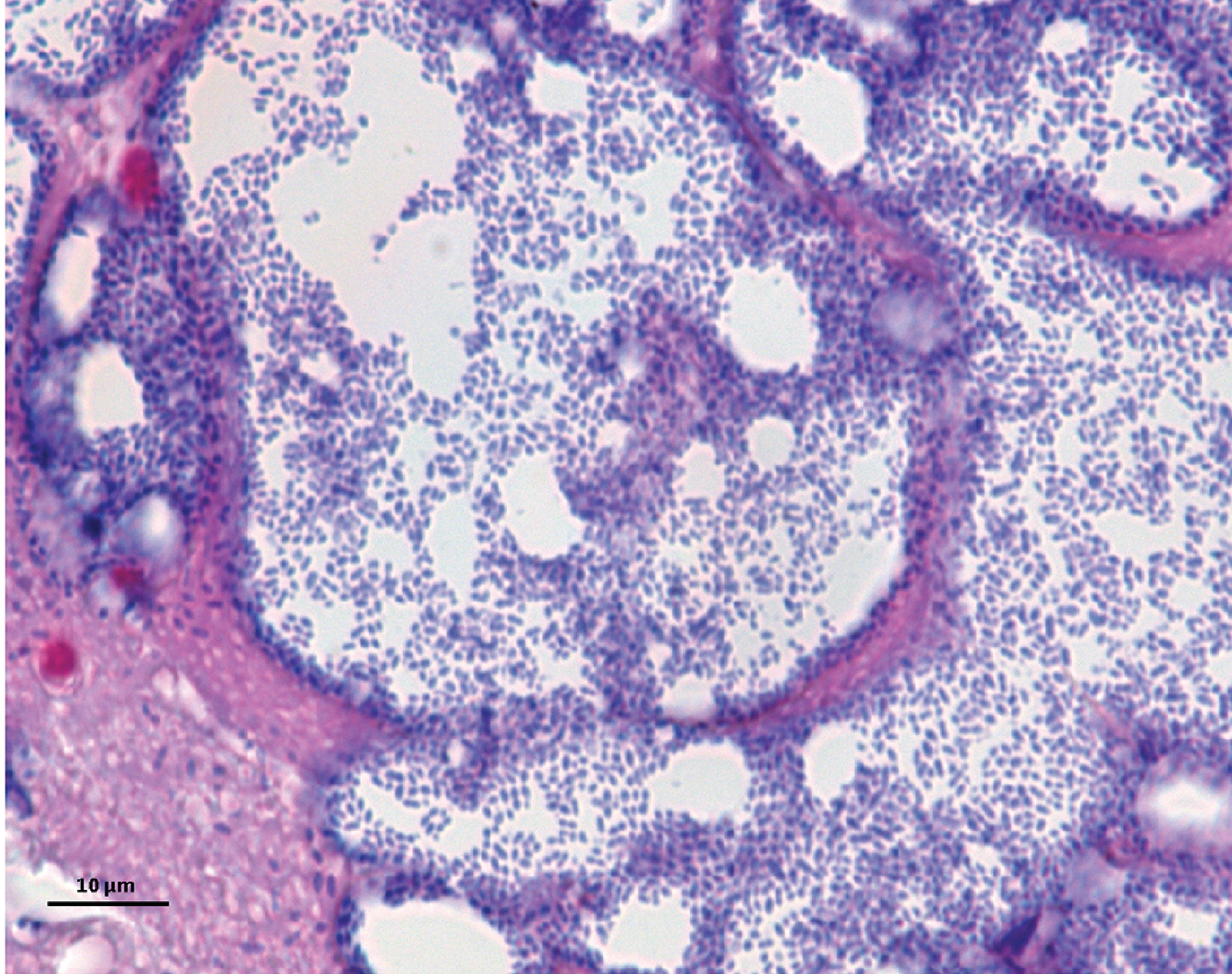

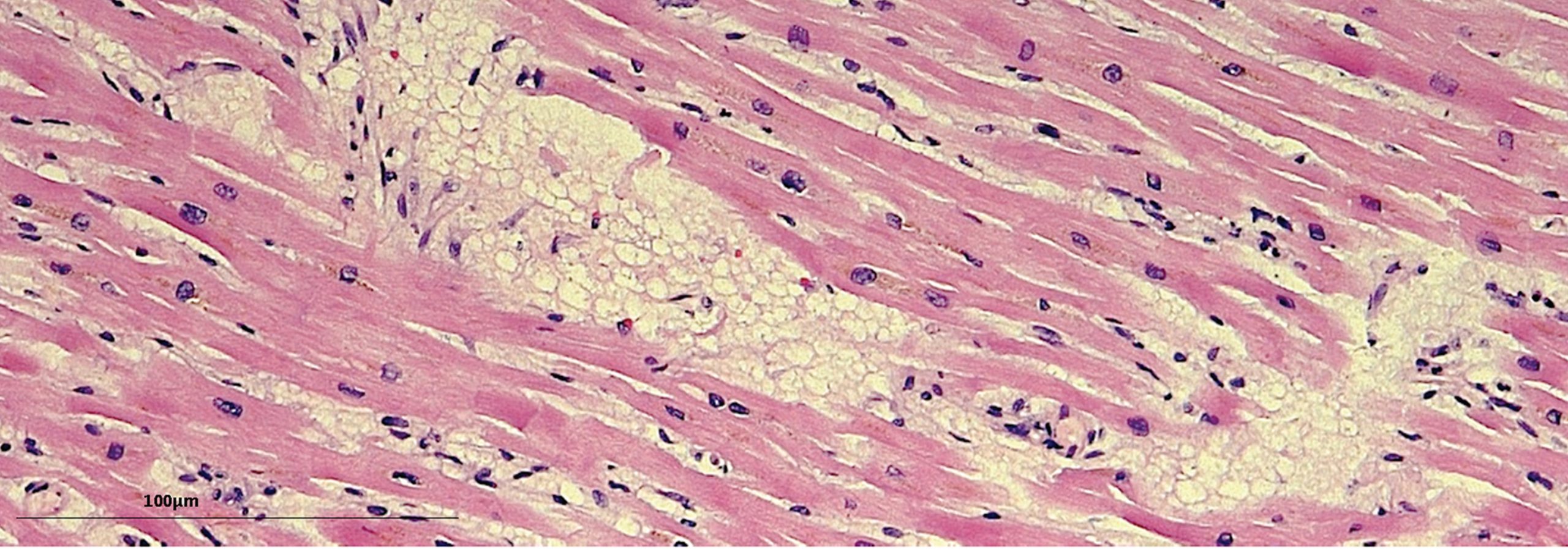

For World Pneumonia Day 2014, PLOS Pathogens interviews Associate Editor, author, and researcher Carlos J. Orihuela on his recent publication in PLOS Pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae Translocates into the Myocardium and Forms Unique Microlesions That Disrupt Cardiac Function, describing how the disease can lead to heart damage in the elderly.

World Pneumonia Day focuses primarily on childhood pneumonia, however your recent paper with PLOS Pathogens, Streptococcus pneumoniae Translocates into the Myocardium and Forms Unique Microlesions That Disrupt Cardiac Function centers on older convalescent individuals. Why is it important to continue research on pneumonia in people of all generations?

The most obvious reason is because everyone matters. Worldwide respiratory tract infections are the leading cause of infectious death in children and the elderly; to focus pneumonia research on just one age group would be to ignore what is a major problem for the other. The principle reason children and the elderly are susceptible to community-acquired pneumonia is because the immune system fails to contain and clear what are normally commensal bacteria; yet the reasons for this in young children and the elderly are very different. Infants have immune systems that are not yet fully developed, whereas the elderly have immune systems that may be unresponsive or dysfunctional in their response to pathogens. Most often, the elderly have underlying co-morbidities. As such, to understand how and why infectious disease progresses, and thereby find ways to prevent pneumonia, we should and need to study the disease in the young and elderly.

Your study focuses on invasive pneumococcal disease, or IPD, what is the difference between IPD and non-invasive pneumococcal disease? What other illnesses fall within this category?

Invasive pneumococcal disease is when the bacteria are able to escape from the lungs and enter the bloodstream and other bloodstream accessible organs. IPD includes pneumonia with bacteremia, bacteremia and sepsis, and meningitis. Non-invasive diseases caused by the pneumococcus include eye infection, sinusitis, otitis media, and pneumonia, the latter of which can also be very severe.

You mention meningitis as an IPD, and your study also mentions that the microlesion formation found in cardiac tissue was dependent on CbpA/LR and ChoP/PAFR interaction, which are the same interactions found in the development of pneumococcal meningitis. How are these illnesses similar and is there anything researchers have learned from pneumococcal meningitis that can help treat these cardiac microlesions?

To me, this is one of the most exciting observations of the paper. In fact, the mechanisms by which the pneumococcus crosses the vascular endothelium into the heart seem so far to be the same for how the pneumococcus crosses the blood brain barrier to cause meningitis. This suggests that agents such as vaccines and drugs developed to prevent meningitis may also stop the formation of cardiac microlesions. Likewise, our research going forward to prevent cardiac microlesion formation may be informative to those who study meningitis.

Can young people with IPD also experience adverse cardiac events similar to those found in older people infected with IPD? What about older people would make them more susceptible? Does a previous history of adverse cardiac events make one more prone to IPD infection, or more prone to adverse cardiac events like these after initial IPD infection?

We suspect that cardiac microlesions can occur in any individual who experiences sustained bacteremia for a sufficient period of time. The reason the elderly are more susceptible to these types of infection is they most often experiences pneumonia that develops into bacteremia and sepsis. I don’t think that a previous history of adverse cardiac events would specifically make an individual more prone to the formation of cardiac microlesions, although cardiovascular disease is a risk factor for pneumonia. Yet, if you have pre-existing cardiac conditions, one could imagine that the development of even just a few microlesions during pneumonia would exacerbate that condition and perhaps more quickly lead to a serious adverse event.

Your paper mentions the potential for a vaccine to protect against microlesions and cardiac damage. Can you explain who would be vaccinated and when? And would this be a new vaccine or an existing ones?

The vaccine formulation described in the paper is a combination of pneumolysin toxoid with two fragments of the pneumococcal adhesin CbpA attached to each end. Thus, you develop neutralizing antibodies against the toxin that kills cardiomyocytes and the adhesin that targets the bacteria to the vascular endothelium. This vaccine antigen called YLN has been shown to protect mice against death caused by experimental pneumococcal disease. It is important to note that the current conjugated vaccine against Streptococcus pneumoniae works extremely well. However, it only protects against the serotypes that are included in the vaccine formulation. Currently in the United States that is 13 of over 90 different serotypes. Because of cost related issues, it is unrealistic to think that we will create a conjugate vaccine that protect against all serotypes anytime soon. As such, we envision that our vaccine will be added to the existing conjugate vaccine formulation. This way, the vaccine would protect against the most important serotypes by eliciting antibodies against their capsule, pneumolysin and CbpA, but also it would protect against all the other less frequent serotypes via antibodies against pneumolysin and CbpA.

You and your colleagues mention that it is still unknown why immune cells are not recruited during severe pneumococcal infection and therefore further replication of the bacteria and further growth of the microlesions is allowed. Are there any speculated reasons why this happens or any leads on how to combat it?

A great question, and one we don’t know the answer to but are working hard to get. We are currently cutting out cardiac microlesions using laser capture microdissection and hope to isolate bacterial RNA from these lesions. Once we have the transcriptome of pneumococci within the lesions we’ll know a lot more about what they are doing and hopefully be able to discern how they are escaping immune detection.

Dr. Carlos J. Orihuela has worked with Streptococcus pneumoniae since graduate school. He received his PhD from The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston in 2001 and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee in 2005. He is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Dr. Carlos J. Orihuela has worked with Streptococcus pneumoniae since graduate school. He received his PhD from The University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston in 2001 and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee in 2005. He is currently Associate Professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.