Chlamydia trachomatis –Urgent need for an effective T cell vaccine to combat the silent epidemic of a stealth bacterial pathogen

Toni Darville from the University of North Carolina considers the potential for a successful T cell vaccine to combat the silent epidemic of Chlamydia trachomatis.

Chlamydia trachomatis accounts for ~100 million genital tract infections in industrialized nations annually, and continues to be the most frequently reported bacterial sexually transmitted infection in the United States. The majority of genital infections in men and women are asymptomatic, and thus go undetected and untreated, likely contributing to its high prevalence. When symptoms do occur, they are often mild and consist of urethral discharge in men, vaginal discharge in women, and painful urination in both sexes. Even the disease that occurs in newborns born to infected mothers is subacute, consisting of eye discharge and lung infection with a nagging chronic cough but a striking absence of fever. Despite its frequent stealth-like nature, it can cause severe reproductive tract sequelae in women when it ascends from the cervix to the uterus and oviducts, causing inflammation and chronic tissue scarring that can lead to chronic pelvic pain, life-threatening ectopic pregnancy, and infertility.

The women who are at greatest risk for infection and reproductive sequelae due to C. trachomatis are the least able to pursue therapies that can overcome the effects of oviduct scarring and enable successful conception and delivery of a baby. Although C. trachomatis infection crosses racial and socioeconomic boundaries, its prevalence is highest in uninsured and socially disadvantaged teen-aged young women. Adolescent girls may sustain an untreated infection for months, and even if their infection is detected and treated with antibiotics, exposure from their untreated original partner or a new infected sexual partner often results in repeated infection because the immunity that develops with natural infection is partial and short-lived. When these girls mature to women and desire to start a family, they discover they are infertile due to the presence of chronic oviduct scarring. These women are rarely able to afford assisted reproductive technologies that are available to the economically advantaged.

Although screening and antibiotic treatment programs have been successful in reducing reproductive morbidities in women, such programs are extremely expensive and difficult to maintain long-term. Furthermore, in areas where widespread screening and treatment programs have been instituted, the rate of repeat infections has risen, suggesting that early treatment may lead to blunting of the adaptive immune response. Thus, a vaccine that prevents infection completely, or results in immunity effective at lowering the bacterial burden sufficiently that ascension of infection to the uterus is prevented in women, is urgently needed.

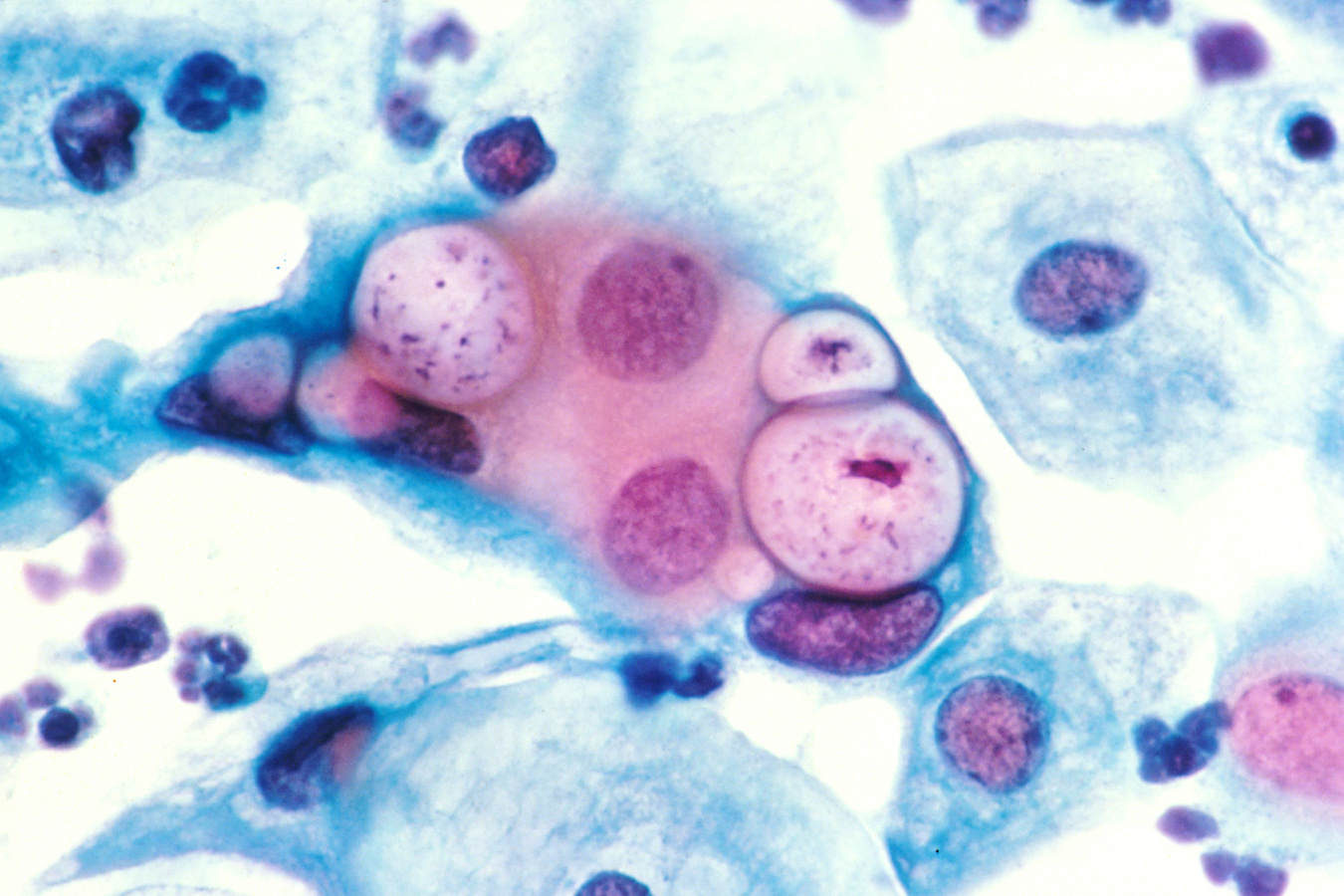

Chlamydia is an evasive pathogen, growing and multiplying in a protective vacuole within the host cell cytoplasm before the immune system has a chance to react. The process of host cell uptake is so efficient that host defense mechanisms active at mucosal surfaces, such as antibody neutralization and neutrophil or monocyte phagocytosis and killing, are unable to prevent infection.

However, there is hope; the natural human immune response is able to eventually eradicate infection, indicating protective immune components develop. A longitudinal study revealed that women who effectively eliminate their infection without antibiotic treatment are also able to resist reinfection later on, providing further evidence of the potential for protective immunity to be achieved. Evidence from animal models and humans indicates that IFN-γ–producing, Chlamydia-specific CD4 (Th1) cells are the primary mediators of protection. In women with HIV, disease risk correlates inversely with CD4, but not CD8 T cell numbers and mice genetically deficient for CD4 or Class II sustain persistent infection and severe disease, whereas CD8 T cells are dispensable. However, the role of CD8 T cells in resolution and protection from infection in humans is under-studied and an improved understanding of both human CD8 and CD4 T cell responses is needed.

The potential for generation of protective immune responses by a chlamydial vaccine is supported by data from animal models, where administration of live, attenuated chlamydial strains leads to partial immunity from reinfection, and significant protection from disease. The risk of reversion to virulence makes the prospects of a live attenuated vaccine for prevention of chlamydial genital infection untenable. However, a subunit vaccine that combines chlamydial antigens with adjuvants that induce protective CD4 T cell responses is an attractive goal. A longitudinal analysis of sex workers revealed that IFN-γ responses by peripheral blood mononuclear cells to chlamydial HSP60, and not to whole inactivated chlamydiae, were associated with protection from reinfection. Additional studies that examine antigen-specific T cell responses in hosts with evidence of natural immunity to Chlamydia are needed to generate data essential for vaccine development. Lymphoblastoid cell lines as an enhanced source of antigen-presenting cells; high throughput immunological assays which use robotics to enhance reproducibility; bacterial gene expression systems for antigen expression; multiparameter flow cytometry to detect specific immune cell phenotypes and cytokine responses induced after antigen exposure— all have the potential to provide a roadmap for rational design of a chlamydial vaccine in the near future.

Longitudinal immunological and molecular studies of exposed women are also needed to identify the women who would most benefit from a vaccine, as well as define surrogate markers of protection. The extreme efficiency of chlamydial uptake into mucosal epithelial cells may make induction of sterilizing immunity via vaccination extremely difficult or impossible, and evaluation for long-term sequelae would be cost prohibitive. Thus, vaccine efficacy testing will require surrogate markers of protection from disease. The sensitivity of blood microarray and microRNA analyses for transcriptional changes induced by infection-induced inflammation can yield blood biomarkers that can serve as surrogate markers of vaccine efficacy and identify minimally symptomatic and even asymptomatically infected women at increased risk for disease.

Although antibiotic treatment can effectively cure Chlamydia infection, Chlamydia’s covert behavior has resulted in a worldwide pandemic of infection among teenagers and young adults. Disadvantaged women bear the brunt of infection-induced infertility and they cannot afford to pay for corrective therapy. A vaccine which prevents ascension of infection to the upper genital tract of women is a viable goal with the use of new immunological methods to define antigens and adjuvants that drive protective T cell immunity. Since sterilizing immunity is not likely an achievable goal, blood biomarkers of upper genital tract inflammation are essential for monitoring vaccine efficacy.

Dr. Toni Darville is a Professor of Pediatrics and Microbiology/Immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she is the Vice Chair of Pediatric Research and the Chief of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. The ultimate goal of her lab is to develop a vaccine to protect against Chlamydia trachomatis infection, focusing on both pathogenic mechanisms of female reproductive tract, as well as induction of protective immunity.

Dr. Toni Darville is a Professor of Pediatrics and Microbiology/Immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she is the Vice Chair of Pediatric Research and the Chief of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. The ultimate goal of her lab is to develop a vaccine to protect against Chlamydia trachomatis infection, focusing on both pathogenic mechanisms of female reproductive tract, as well as induction of protective immunity.

[…] Toni Darville from the University of North Carolina considers the potential for a successful T cell vaccine to combat the silent epidemic of Chlamydia trachomatis. Chlamydia trachomatis accounts for ~100 million genital tract infections in industrialized nations annually, and continues … Continue reading » […]