By guest contributor Dr Soumya Swaminathan Women and girls account for 50% of the population. Despite this, health systems are ill-equipped to…

Is global health ignoring global human development?

By guest contributor Themrise Khan

Global health has dominated world headlines since the emergence of COVID-19. More so at times, than other world events like war, famine and even terrorism. Rightly so. Health has long been a neglected human right. But the discussion on global health as a result of COVID-19 has one drawback. It is eclipsing, and as a result, doing a disservice to the various intersections of human development.

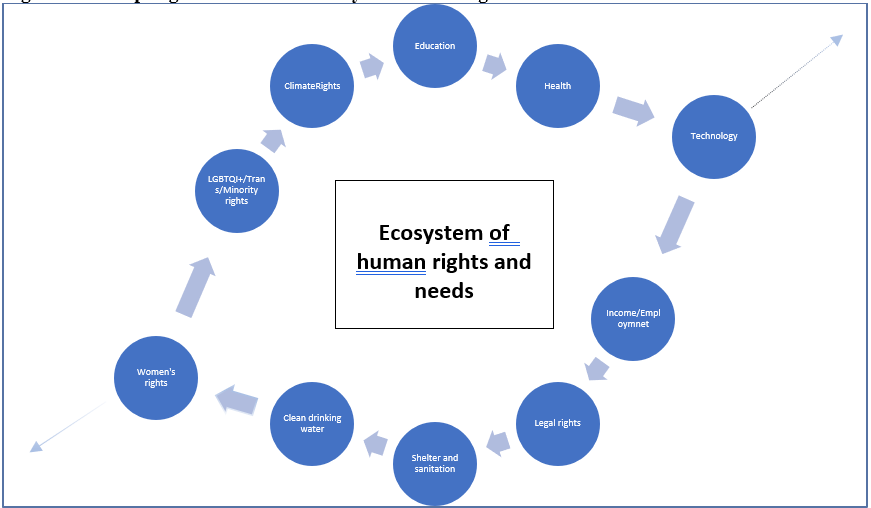

Global health, like any other human right, is only one component of a larger whole that forms our human development ecosystem. Basic rights and services like education or access to modern day internet are interconnected. Whatever affects one component affects the other. Disconnecting one component leaves a gap that can be filled by an ever-increasing roster of rights constantly squeezing themselves in, but can also lead to one right being usurped by another (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Disrupting the Interconnectivity of Human Rights (created by the author)

*further rights such as free human movement, refugee rights etc. can be added to this ecosystem.

Due to the spread of COVID-19, global health can be seen as usurping many of these rights which were ignored over the panic surrounding the pandemic. Lockdowns and associated precautions such as social distancing and hand washing, ignored the lack of housing and personal space in most low-income neighborhoods and lack of access to clean water (or water in general), respectively. Vaccine inequity aside, rights to legal status required for registration for vaccination, was affected by bureaucratic and discriminatory procedures faced by minorities, refugees and even women. Closure of schools led to not just children being out of school, but being unable to access online resources due lack of access to technological hardware and software and even electricity. Loss of employment due to immediate and extended lockdowns was influenced by a corresponding absence of long-term social safety net provisions, especially for the poor.

A more recent example showing the emphasis of what I term “the global health creep”, was the denial of visas by Canada to several delegates from middle- and low-income non-Western countries, from attending the AIDS 2022 conference. While this is highly condemnable, the issue was less about closing borders to global health specialists from the non-West and more about racist and restricted borders in general.

There are many similar examples that can be invoked to show how an over emphasis on global health is consuming the space of other basic rights such as; affordable housing, water and sanitation, legal status, gender inequality, lack of access to technology, social safety nets and free movement, among others. All part of overall human development.

These are issues that have been prevalent across many countries for decades. And not only in those that are classified as low income, but in all countries at varying levels, and they are not new. Many diseases such as cholera and hepatitis are directly related to contaminated water sources. Likewise, access to basic health is restricted for many women due to archaic cultural and social norms. Corporate profiteering by pharmaceuticals, is not the sudden result of Pfizer and Moderna monopolizing the COVID vaccine. And perhaps, most obvious of all, is the existing inequality between rich Western nations and lessor-rich nations in Africa, parts of Asia, the Middle East and Latin America, as a result of colonialism.

By and large, discussions on these issues have been front and center since the pandemic. But only so because they now impact on global health policies and practices vis-à-vis the pandemic itself. Credit should be given as it continually is, that COVID-19 has brought several inequalities to the forefront. But one cannot only advocate for one component of the ecosystem over another because it was connected to a global catastrophe. It is like saying that climate change is important because it only leads to a spread of diseases. Or that the global financial collapse of 2008 affected only the stock market.

As such, it was not the lack of access to and importance of global health which exacerbated issues during the pandemic. It was a lack of attention to issues outside the global health mandate which exacerbated pandemic preparedness. This does not diminish the importance of global health by any means. But it shows that global health services, research and preparedness must be consistently connected to research and outcomes of other basic human rights to be relevant and efficient. The global health community cannot demand universal access to vaccines, but ignore the rights of affordable housing or access to education. And this applies vice versa to all other components as well.

Given this approach, global health and pandemic preparedness have taken a primarily one-dimensional view of society and how it operates. Had interconnectivity driven the provision of basic services, perhaps we would not have witnessed such an unprecedented breakdown during COVID-19. And perhaps we may have been able to come up with more lasting and interconnected solutions as well.

About the author:

Themrise Khan is an independent development professional and researcher with over 25 years of practitioner and policy-based experience in international development, aid effectiveness, gender, and global migration. She has worked with a vast spectrum of multilateral and bilateral organizations, INGOs and civil society organizations in Pakistan, Canada and South Asia and has a number of publications and articles to her credit. She blogs, speaks and writes actively on notions of decolonization, North-South power imbalances in development, race relations and immigrant citizenship and integration. She lives in Pakistan.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by contributors are solely those of individual contributors, and not necessarily those of PLOS.