Could Yellow Fever Return to the United States?

Peter Hotez and Kristy Murray from Baylor College of Medicine highlight the potential for yellow fever to return to the southern cities of the United States

In the summer-fall of 1878 an epidemic of yellow fever destroyed the city of Memphis, Tennessee. Likely introduced into the Caribbean by trade from the West Coast of Africa and later brought up the Mississippi River by a steamer ship (the Emily B. Souder) with sick and dying sailors, yellow fever killed an estimated 5,000 Memphis residents, almost one-third of its population who did not flee the city that August [1]. According to Molly Caldwell Crosby in her detailed account, the summer-fall 1878 yellow fever epidemic in the Mississippi Valley was possibly “the worst urban disaster in American history” [1].

Among the factors responsible for the 1878 tragedy were an unusually warm winter and spring that year, which helped Aedes aegypti mosquitoes to flourish in the Mississippi Valley, together with a lack of adequate urban drainage and a functioning sewer system, and a susceptible (non-immunized) population – the yellow fever vaccine would not be developed for another 50 years.

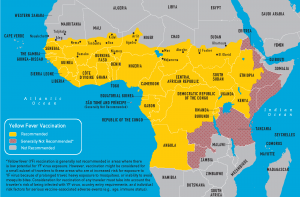

Today, the world’s yellow fever-endemic areas are restricted to Sub-Saharan Africa (figure image) and tropical regions of South America, but there are a few red flags suggesting the possibility that the “yellow jack” (a historical term used to once describe yellow fever) could return to the US. The Ae. aegypti mosquito can now be found in many areas of the southern United States. This is an area where US poverty rates are at their highest, along with its fellow travelers poor urban housing and neglected foci of standing water. The area has also experienced unusually warm winters and springs over the past few years. Indeed, dengue fever, another arbovirus infection transmitted by Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, was recently shown to have emerged in Houston, Texas in 2003. Although Max Theiler received the Nobel Prize for developing the yellow fever vaccine in 1951, vaccination rates in the US are practically non-existent except among travelers to endemic areas.

There are several examples of US vulnerability to yellow fever, including our home city of Houston, which has recently emerged as a true gateway city and globalization hub. For instance, today, Houston hosts the world’s largest number of Nigerian expats (who provide important and skilled expertise for our city’s oil and energy industry), and there are direct flights to and from Lagos, the largest Nigerian city. A recent study from the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine of the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) found that US travelers to Nigeria are especially likely to decline vaccination, despite the fact that its urban areas are at especially high risk for yellow fever outbreaks. The culmination of travelers returning to Houston from endemic areas, subtropical climate, high prevalence of Ae. aegypti mosquitoes, and areas of dense housing overlapped with poverty place Houston at risk for yellow fever emergence.

We need to seriously evaluate the risks of the major southern cities of the US, including Houston, but also New Orleans, Tampa, and Miami for their vulnerability to Aedes-transmitted arbovirus infections, such as yellow fever. As we have pointed out, cities such as Houston have emerged as important endemic zones for neglected tropical diseases. While we are aware that US urban areas may not be as vulnerable to yellow fever as Memphis was more than a century ago, there is still an important risk that needs to be considered as part of our national emergency preparedness, particularly in light of an emerging dengue problem (i.e., another Ae. Aegypti mosquito transmitted virus infection) in Houston and other southern coastal US areas.

References

- Crosby MC (2006) The American Plague: The Untold Story of Yellow Fever, the Epidemic that Shaped our History Berkley Books, New York, pp 74-75.