Cancer Genomics: Data, Data and more Data

PLOS Medicine’s Senior Research Editor, Clare Garvey, recently caught up with Francis Ouellette, the Associate Director of Informatics and Biocomputing at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) to find out about progress in cancer genomics, the issues surrounding the tsunami of data that has been generated by The Cancer Genome Atlas Project (TCGA) and the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), and how developments may impact clinical care for cancer patients.

This interview accompanies the editorial appearing in this week’s PLOS Medicine.

Francis, can you tell us what the goals of the TCGA and ICGC projects were and how they are overlapping or complementary?

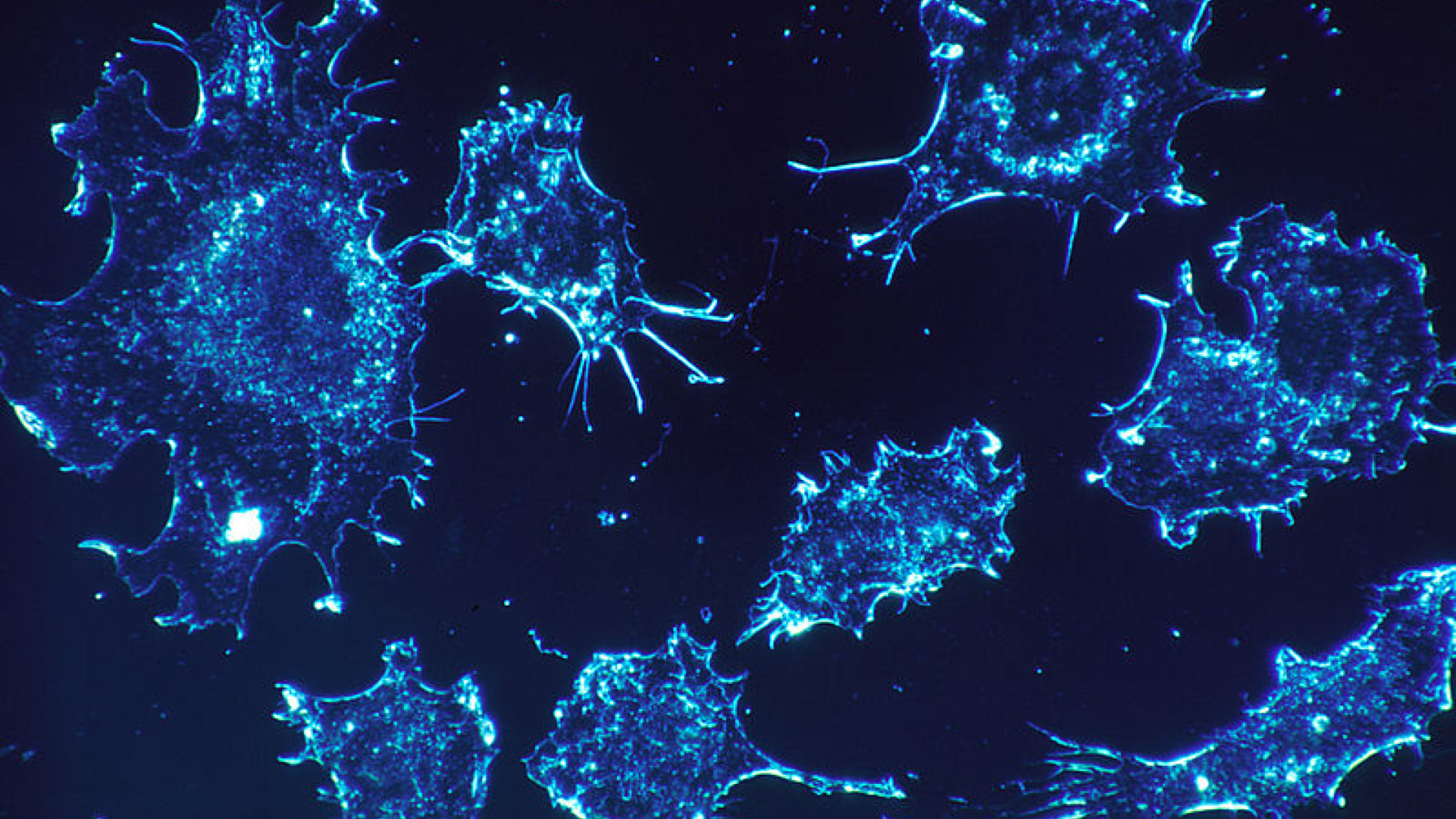

The TCGA pilot was started 2006 and precedes the inaugural ICGC planning working group meeting in 2007 – the ICGC per se started in 2008. Since the beginning, the TCGA has been part of the ICGC. The overall goals of the two projects are similar – to capture the genomic information on tumour types in many different ways: with exome or whole genome sequencing to determine the simple somatic mutations; copy number variations; structural variations and effects on transcriptional regulation that happen in cancer. For this, genomic, mRNA, miRNA, and epigenomic data is collected. The goal of the ICGC has been to capture the genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic and clinical information on 50 different tumour types and for each of these projects, collect 500 tumours and their matched normal DNA sample (commonly from blood, except for leukemias) for each tumour type and so that’s an ambitious goal of 25,000 donors, i.e. 50,000 genomes (tumour and a ‘normal’ wild type match). Approximately half of the ICGC genomes are from the TCGA projects. If you go to the ICGC data portal you will see a list of all of the cancer genome projects that have submitted data to date.

Since the initial plan to obtain data for 50 tumours, additional projects have been added, taking the number to 85 projects. ICGC Cancer Genome Projects support the characterization of 500 unique cases of one cancer type or subtype. Some of the additional projects focus on rare cancers, such as childhood leukemias, and for these rare tumor types we may only get 100 or 200 donors.

Can you tell us about the data that the projects are generating?

The genomic sequences for each of these tumours come in one of two possible flavours: exome, which are the selected genomic sequences that encode mRNA, and whole genome sequence (WGS). We anticipate that in the second part of the project the needle will swing away from exomes and over to more whole genomes being sequenced as these becomes more affordable.

A few projects have submitted germ-line variants and these are only available if you have DACO credentials for controlled access data. The controlled access data is restricted to protect patient privacy and is controlled by two different bodies which are under different ethical and legal jurisdictions: those for the non-NIH-funded ICGC datasets and those of the NIH-funded TCGA datasets that can only be held in NIH trusted partner sites for cancer genomes, namely CGHub and the University of Chicago.

One interesting point about the simple somatic mutations that are identified and presented on the dcc.icgc.org website are computed by each individual submitting genome centre. These “calls” from different groups will have used different algorithms to determine these mutations. Users need to take this into account when interpreting these mutations, but the recently announced Pan-Cancer project is addressing this currently.

What’s next for these projects?

These projects are planned to run for 10 years, so from 2008 to 2018. Each of the 50 projects cost 20 million US dollars to fund, that’s a billion dollars in total. A billion dollars to do 50,000 genomes is still better value for money than the first single genome that was sequenced for $US1 billion, and the ICGC initiative also includes all the other data types, such as transcriptome, epigenomic and clinical data. There is also added value in that we are running an initiative called the Pan- Cancer analysis of more than 2,400 whole genomes where we realign everything by one standard operating procedure. We are also validating a subset of the “called” mutations with experimental data to ensure that calls are being made correctly. We will be posting the results from the Pan-Cancer analysis on the ICGC data portal once we are finished that study.

How are the projects translating this information into healthcare?

There is a big and unaddressed problem when it comes to the training of physicians and clinicians and how to interpret data into care: it’s one thing to create data but if clinicians can’t interpret and use it, then it’s not very useful. The scope of TCGA and ICGC does not include training for clinicians, but we, at the OICR, do consider how the data could translate in to actionable activities that will help cancer patients. If robust reproducible pipelines could be developed where the detection of a given mutation type could instruct a clinician to provide treatment X, then we will have accomplished a laudable goal.

Training and education is more challenging on an international level. It needs to be addressed on a national level and so each country has a responsibility to make sure this happens. For example, a paper from a project could be published in two journals. For example, the data paper could be published in PLOS Computational Biology while the accompanying medical and clinical paper could be published in PLOS Medicine.

The preface of these projects is that cancer is a disease of the genome. You don’t treat a tumour type; you treat the genome, and the driving genomic aberrations it harbours.

The next 5 years?

Genomics is becoming more focused on personalized genomics. ICGC is thinking about the next project and so we are at initial stages of discussions, but the next stage will include how individual tumours evolve over time and linking to clinical trials and will be on a larger scale. One of the big challenges we identified while working on the Pan-Cancer genome project is the need for more computational infrastructure: moving to whole genome analyses will require more infrastructure as there is much more data. Doing the analyses is quite challenging and time consuming already, so as these projects scale, we will need to think about hosting datasets and analyses in cloud infrastructure rather than multiple venues or downloading data to individual desktops or even their institutional high performance computing centres. In addition, hospitals are silos into this ocean of data sharing, so hospitals will need to work with these projects it will be even more critical then ever to share the clinical data (an important issue addressed by the Global Alliance for Genomics and Health). We’ll need to also make these data as open as possible. Essentially there needs to be more ‘eyeballs on the data’. The more people who look at the data, the more discoveries will be made and we need to avoid limiting or making this difficult. It would be a great system if we could have a trusted scientist system so that all of the bodies that oversee and protect access to clinical and genomic datasets come together to classify someone as a trusted scientist – allowing her or him to access all datasets. This is the way that more discoveries will be made and how a project like the ICGC (and many more to come in the future) can be of greatest benefit to society.

Francis Ouellette, Associate Director of Informatics and Biocomputing at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and Education Editor for PLOS Computational Biology.

[…] PLOS Medicine’s Senior Research Editor, Clare Garvey, recently caught up with Francis Ouellette, the Associate Director of Informatics and Biocomputing at the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (OICR) to find out about progress in cancer genomics, the issues surrounding the … Continue reading » […]