In this post, we speak to the authors of a recent PLOS Global Public Health article, “Crises are a perpetual restart” – a comparative…

You are a Global Health Professional, and You Don’t Know It

By guest contributors Chiamaka P. Ojiako and Madhukar Pai

What’s in a name? That which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as sweet.

William Shakespeare’s play “Romeo and Juliet“

Adrianna, a Sierra Leonean doctor, provided maternal health care services to pregnant women and new mothers in hard-to-reach communities for over two decades. She later relocated to the United States for a graduate program, and eventually secured a job designing maternal health programs for an international NGO based in the US. Suddenly, the work she had done for years back home was elevated to global health status. Until her move to the US, she had never considered her work to be “global health” and is fascinated by how simply moving countries led to a change in label or perceived status.

Jason is a recent MPH graduate from a Canadian university. He joins the local city health department and works on routine vaccination programs. After a couple of years, he gets a chance to work for a Geneva-based organization that supports child vaccination programs in Africa. He notices that he is now being called a global health professional.

Adrianna and Jason’s stories echoes so many people’s reality; an unspoken dynamic around the ‘global health professional’ label and who a global health “expert” is that people encounter and embrace despite its nebulous origin and inconsistent application. It begs for deeper exploration, and we invite you to unravel this mystery with us.

Let us say, for the purpose of discussion, that global health professionals are people that work with the World Health Organisation and multinational organisations on health programs and initiatives. If that is the case, then why does the goalpost shift when certain professionals move to other countries to work on health matters? Are there locations one must originate from or move to, in order to qualify for that label? And if yes, where was this decision made and who agreed to it?

Let’s take it a step further by limiting the label qualifiers to people with a degree in medicine, global or public health. This restrictive definition only holds if global health professionals didn’t exist before medicine, global or public health programs and that is not the case.

These questions become especially pertinent to ponder considering the current state of affairs in global health where countries are shifting toward country-first, nationalistic policies for health programs, drastic cuts in aid budgets for health, and immigration policies geared towards othering and tightening borders. While we mourn the devastating impact of these changes, they also present an opportunity to pause and reflect.

If professionals who move from the Global North to execute health programs in the Global South qualify as global health professionals, then surely the nurses, healthcare workers and public health and health policy professionals who migrate from the Global South to apply their skills and expertise towards strengthening health systems elsewhere should qualify too. If not, why not?

If funding is the qualifier, then we can be honest with ourselves. If your country funds health programs (i.e. is a “donor”), you are elevated to the global health professional status. If you are moving to ‘greener’ pastures, then you are not. That distinction would give us a clear sense of where to direct our questions and who to channel our grievances.

Why does this even matter?

Labels and names are elevators in the health sector and could make the difference between being treated humanely or as a liability that needs to be done away with.

Labels and names are elevators in the health sector and could make the difference between being treated humanely or as a liability that needs to be done away with. The current narrative is that people who move from non-donor countries are immigrants that ‘take jobs’, ‘refuse to integrate’ or ‘pose a threat’. Many of these professionals face dehumanizing experiences that leave life-long damage to their sense of self, especially, in the absence of intentional guardrails to protect their dignity. Going through all sorts of hurdles just to prove their worth. Meanwhile, many professionals who migrate from donor countries are treated with respect as “expats” with much higher salaries, special privileges (including fast-track visas, emergency evacuation during crises, special medical care coverage), are presumed to be knowledgeable and welcomed as value-adders, even when their roles are primarily about coordinating the work local professionals are doing on the ground.

Another interesting dynamic is the inconsistent use of the global health professional label, even when all the parties involved are working on the same donor-funded health program. If professionals from donor countries, who often do not need to migrate, are considered global health professionals by virtue of their affiliation with the program; are the professionals in the recipient countries who are executing that very same program on the ground also global health professionals? If not, why not?

Furthermore, are the professionals who remain in their countries to execute routine, nationally funded health programs also global health professionals? If not, why not?

If the distinction between those who are referred to as global health professionals and those who are not isn’t about migration, geography, or the nature of the work, then what is it really about? Is it based on impact, expertise and system-level contribution or is it more about perception shaped through the lens of funding, geography, and power?

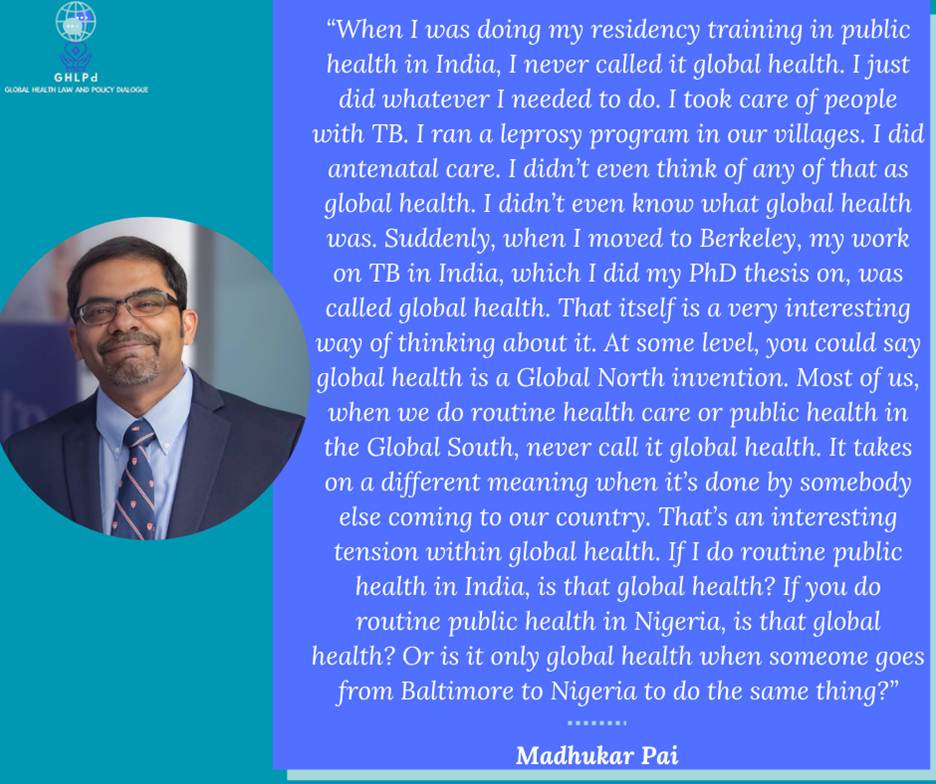

Again, these questions are not abstract but reflective of people’s realities and experiences. A recent LinkedIn post shared a snippet from a podcast conversation with Madhukar Pai on the state of global health.

Here are some of the responses to that post confirming that while the label ‘global health professional’ is rarely discussed it is a befuddling phenomenon that people do not fully grasp.

“This resonates strongly. I was once asked why I chose to do global health and my answer was that I didn’t choose to do global health. What I chose to do was public health, but I got into the US and realized that it was called global health by the people doing it from there.”

“That’s some real food for thought. I became “a global health scholar” when I moved to Canada as an Assistant Professor. Before I was just epi research in the Caribbean. It’s definitely a term we need to rethink.”

“Maybe the impact of an unhealthy neighborhood spreads farther than we realize, like a butterfly effect. We are connected in ways that science can’t always explain or measure. That might sound philosophical, but it is true that we all breathe the same air the air we breathe in one place travels with us anywhere. The definition of global health can be philosophically described as “The impact of health at one place reflects on the global health of the entire world”.”

“What a humbling and thought-provoking take. It is just health, I think, because we are all human.”

“When I saw this post, the words struck a chord within me. Similar to Dr Madhukar, those of us who worked in public health in ‘less fortunate’ countries never really thought of fancy titles or descriptions for the job position and the work we do. For us, it was public health, and the daily grind of addressing the issues and challenges to public health.”

“We already practice Global health (“whatever we need to do”) since the beginning of our career paths (even as medical students or general physicians in social service) in the Global South!”

In the grand scheme of things, a label should not be strong enough to change your qualities or determine your trajectory, but the reality is it does. It impacts who gets to be at certain tables, who earns what, and how people carry themselves.

So, while we do the work to unravel this dynamic and hopefully pinpoint the decision-makers, let’s be clear. Based on logical deduction, all of us are global health professionals wherever we do health work, even if we didn’t know it. Glocal is global!

About the authors

Chiamaka P. Ojiako is a lawyer and health policy professional working at the intersection of law, governance, and innovation in health and development. With experience across public, non‑profit, and international development sectors, her work spans digital transformation for health, ethical data governance, and multi‑stakeholder collaboration. She is the founder and convener of the Global Health Law and Policy Dialogue (GHLPd) network and a strategic partner in policy and governance across the “Big Five” domains; artificial intelligence (AI), joined‑up data, genomics and predictive analysis, wearable technologies, and robotics. Connect with her on Linkedin and Twitter @FavouredAmaka

Prof Madhukar Pai, MD, PhD, FCAHS, FRSC is the Inaugural Chair, Department of Global and Public Health at the McGill School of Population and Global Health. He holds a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Epidemiology & Global Health. He was Director of the McGill International TB Centre. He was previously Editor-In-Chief of PLOS Global Public Health.

Disclaimer: Views expressed by contributors are solely those of individual contributors, and not necessarily those of PLOS.